1. Introduction

The demand for micro-credentialing arises from the need to provide students with a clear indication of their expertise in specific subject areas. Higher-education instructors seek to develop this capability, as traditional grade point averages (GPAs) and letter grades often fail to accurately represent student competency in particular disciplines. This lack of clarity can have significant implications for both academic and professional pursuits, necessitating targeted remediation and future employment opportunities.

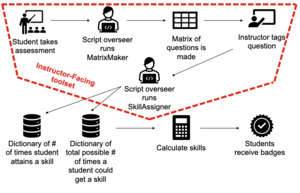

While micro-credentialing has gained traction and is an active area of research, various methodologies have been explored to achieve similar goals. However, these approaches often have limitations. A common challenge is the reliance on students completing skill-specific assessments or courses, which can be time-consuming for instructors to develop and for students to complete within their already demanding schedules. The taxonomy presented in Figure 1 illustrates multiple pathways for conducting detailed analyses and their respective roles in higher education.

Micro-credentials may be categorized into two primary types. The first type involves completion-based assessments, which can be found on platforms such as Badgr, Accredible, and Credly. In this approach, students earn recognition primarily by successfully completing skill-specific assessments or a series of assessments. The other category is the skill-specific program route, which often consists of specialized courses offered to university students or individuals seeking skill-centered education in a non-traditional context. While these methodologies are functional, they may have limitations that make developing and taking courses more cumbersome. Specifically, they focus on a specific skill topic at a time, rather than providing a comprehensive analysis of global scaled skills. Notably, similar studies share a common goal: to improve the learning experience.

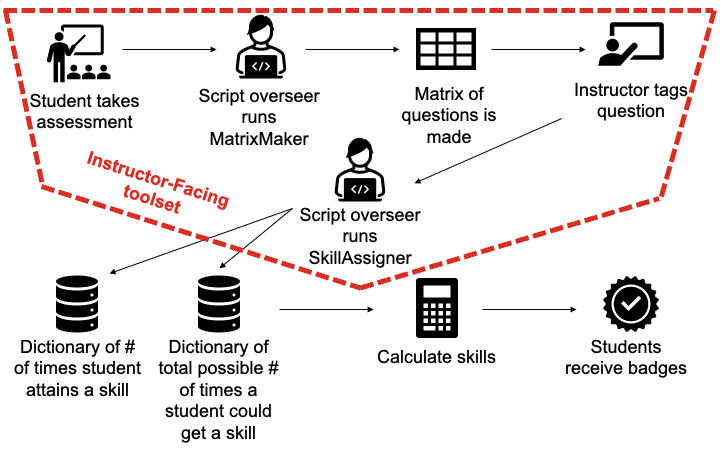

AchieveUp was developed with an NSF grant for Building-the-Capacity Ecosystem (BC-Eco) which leveraged digitized assessments within a loop engaging undergraduate student mentors and industry to automate micro-credentialing of student skills. This facilitates personalized tutoring, peer-mentorship, and internships by utilizing services listed on the left-hand side of Figure 2. The foundational level of BC-Eco is based on micro-credentialing, which utilizes digitized assessment data from 29 STEM courses that were already digitized in the implemented university curriculum between 2014 and 2019.

The success of digitized assessments in the College of Engineering and Computer Science (CECS) and the College of Sciences (COS) at the implemented university has led to the initiation of the multi-disciplinary BC-Eco Project, as depicted in Figure 2. Students enrolled in STEM courses utilizing he BC-Eco embark on a structured pathway, progressing from Student Mentees to Student Mentors, and ultimately to Interns. This upward trajectory is guided by gold-colored arrows presented in Figure 2, starting at the lower-left corner, and encompasses Micro-Credentialing, Peer-Tutoring, and Industry Internship opportunities. One of the three student-facing mechanisms is generating digital micro-credentials from digitized assessment results through an automated process. This is achieved by developing micro-credentialing Python programming language scripts that can be applied via a one-time tagging step to questions within STEM course assessments. The ability to earn digital micro-credentials constitutes the first step for students participating in BC-Eco, making them eligible to become tutoring candidates. For example, a student may earn a digital micro-credential in topics such as Finite Element Modeling or Human Computer Interface Design. This enables collaboration among students who have demonstrated exceptional proficiency, providing support and resources to their peers (Amoruso, 2023; Amoruso et al., 2022).

The AchieveUp framework is designed to provide a nuanced and detailed picture of students’ skills through micro-credentialing, recognizing the limitations of traditional grading systems in capturing the complexity of student learning. By leveraging micro-credentialing, we aim to bridge the gap between academic achievement and employer expectations, offering a more fine-grained understanding of students’ skills and knowledge that can be applied across various disciplines. Unlike traditional approaches to skill recognition, which often rely on coarse-grained assessments and summative evaluations, our framework is grounded in a research-based methodology that seeks to explore new ways of tracking skills in a more granular and transportable manner. This approach has the potential to enhance the validity and reliability of educational assessments, ultimately providing employers with a more comprehensive understanding of the skills and competencies that students possess and creating new opportunities for innovation and improvement in education that can lead to better outcomes for students and employers alike.

The organization of this paper is as follows: Section 2 presents a literature review; Section 3 reviews the micro-credentialing framework methodology and highlights what distinguishes our approach from others, particularly in engineering courses. Section 4 provides an overview of the operational flow. The results in section 5 will include feedback responses from students, instructors, correlations between grades and badges, and correlations between badges and lectures. Finally, conclusions and implications for further research are outlined in Section 6.

AchieveUp solves the challenging obstacle of identifying student achieved skills in a globally scaled manner. More specifically, it can measure student comprehension via the tagging of skills to individual questions rather than whole modules or courses. Furthermore, AchieveUp allows the ability to implement in preexisting digital courses via the tagging of multiple skills to individual questions using a question skill matrix. This allows for implementation onto any online digitized quiz-based courses on Canvas LMS without the need for instructors to change their already digital quizzes. Therefore, it allows instructors to incrementally adjust the course based on the data representation AchieveUp provides. The dispersion of skills to students for instructor benefit and student self-advertisement via digital badges on LinkedIn.

2. Literature Review

The micro-credentialing process was inspired by digital badges used by websites like Stack Overflow, which enable students to showcase specific aspects of their achievements in a more visual and shareable format compared to traditional transcripts or grade-point averages. Micro-credentials can also be used to represent student learning, increase opportunities for expertise through varied learning experiences, and establish learner accomplishment in a holistic manner (Ali & Khan, 2023; National Science Board, 2010). The Mozilla Foundation’s Open Badges Initiative (OBI), established in 2011, provides open-source digital badges that serve as an example of this approach. Similarly, leading companies such as Google may prefer to hire individuals who have completed targeted digital training and earned certifications, rather than relying solely on GPA scores. Industry organizations like Google, Adobe, and Microsoft support valued IT certification-focused programs that hold significant regard within the field (Gerstein & Friedman, 2016).

2.1. Completion-Based Micro-Credentialing Approach

In higher education, the practice of awarding badges and implementing micro-credentialing is not a new concept. Companies such as Badgr, Accredible, and Credly have taken the lead in this area, providing badge-based solutions that aim to authenticate skills, increase student involvement, enhance graduation rates, and drive enrollment numbers (Canvas Credentials Digital Badges for Higher Ed, n.d.). However, these solutions often miss the primary objectives outlined in this paper.

Badgr enables instructors and course designers to manage badge requirements, review private leaderboards, and employ features like learning pathways to motivate students. It provides a gamified view of badge acquisition through a leaderboard, tracking individual student performance. Badgr allows instructors to award badges based on overall course grade, completion, module fulfillment, or assignment performance (Canvas Credentials Digital Badges for Higher Ed, n.d.; Digital Credential Network Powered by Badgr Pro, n.d.). Following its acquisition by Canvas in 2022, Badgr became an academic product and was integrated into the Canvas Learning Management System (LMS) (Mallon, 2019).

Accredible offers features such as automated badges and certificates, native badge viewing within Canvas LMS, and single sign-on for automatic authorization. Like other products, Accredible relies on instructors to utilize topic-based modules to determine students’ credential eligibility. The company emphasizes close integration with the LMS for ease of use (Canvas Badges & Canvas Certificates, n.d.). However, it may require course modification to set modules to specific course topics.

Credly by Pearson introduces digital credentials that mimic classroom engagement, visually displaying students’ course accomplishments. Beyond badges, Credly aims to help the workforce understand employees’ skills, anticipate future positions, and enhance recruitment. It operates as an LTI application in Canvas, awarding badges for discrete assignments or modules upon completion, like Badgr and Accredible (Author Credly Team, 2022; Credly, n.d.).

In contrast to these existing solutions, this paper presents three distinguishing features: minimal intrusion for implementation within existing courses, the capacity to tag multiple skills using standard digital quiz-based assessments, and a user-friendly interface requiring minimal learning. Moreover, micro-credentialing opportunities offer new tangible incremental outcomes for students’ résumé and LinkedIn profiles.

Table 1 catalogs the various features for each of the major fine-grained analysis organizations and shows that the research presented trades the tagging of skills to assessments or modules for tagging of questions.

Correspondingly, Table 1 presents some software frameworks available for issuing and managing academic badges. These platforms were evaluated by the project team based on factors such as extendibility, API design features, data robustness, and popularity. It is worth noting that the Open Badges development project is not a platform in itself (Buckingham, 2014; Elevate Your Learning with Open Badges, n.d.; Ortega-Arranz et al., 2019), but rather support badges dispersed via platforms such as Badgr. In fact, while badge categories are open source across all platforms, not every software platform issuing badges offers easy extensibility.

The NSF Python script-based framework analyzes student performance on a question-by- question basis. For each student and for each badging category, the software framework examines student responses to determine if student responses to those questions were correct up to the threshold set by the instructor. The goals presented in the related research are similar in scope to the approach outlined in this document. While the solutions discussed in the existing literature work well for their specific niche scenarios, the goal of this solution was to provide a versatile methodology that can be applied to nearly any STEM course using online assessments. The hypothesis was that by accurately identifying student skillsets, it is possible to offer students an opportunity to differentiate themselves in the job market and potentially match them with peers who complement their strengths.

2.2. Skill-Specific Micro-Credentialing Program Approach

Several methods exist for conducting in-depth assessments of student competencies, providing detailed insights into skills acquired during courses. The State University of New York’s (SUNY) Micro-Credentialing Task Force evaluated a methodology to implement micro-credentials in higher education at the institution. This initiative combines SUNY course materials with workshops, traditional coursework, applied learning experiences, and certification training. Designed not only for current students and alumni but also for individuals seeking to enhance their resumes (Microcredentials - SUNY - State University of New York, n.d.), SUNY micro-credentials aim to make credentials accessible to a wide audience, necessitating the development of skill-specific courses separate from accredited programs.

Penn State University’s Information Literacy Badges program introduced 10 digital badges, supported by Mozilla’s digital badge backpack, enabling undergraduates to showcase their achievements (Badging Essential Skills for Transitions (B.E.S.T.): USM Center for Academic Innovation, n.d.; Canvas Badges & Canvas Certificates, n.d.). The approach involved designing courses centered around specific skills. Each badge comprised a series of steps, with instructors specifying the content and criteria for each step. Furthermore, the Penn State University Library’s information literacy digital badging initiative required students to provide evidence for a badge, which was then reviewed by a librarian or instructor to offer feedback on any necessary steps to earn the badge (Library Guides: Online Students Use of the Library: Information Literacy Digital Badges, n.d.).

The Badging Essential Skills for Transitions (B.E.S.T.) system, adapted from the University System of Maryland (USM), introduced the process of awarding badges to students, utilizing Credly as the platform for creating and distributing digital badges. USM institutions piloted badge programs with selected students who had to meet specific criteria and rubrics to earn badges. However, the system adopted a broad approach, offering generalized badges to multiple institutions. Notably, The Universities at Shady Grove led in the distribution of badges in 2018, offering three badges to an entire institution for students in specialized courses. These badges covered broad skills such as communication, critical thinking, and intercultural understanding (Badging Essential Skills for Transitions (B.E.S.T.): USM Center for Academic Innovation, n.d.).

The OpenBadges website, developed by Mozilla, serves as a tool for instructors and others interested in awarding badges to individuals who complete badge-worthy tasks. It offers functionality for creating, managing, and distributing badges to students or anyone seeking to enhance their digital resume (Elevate Your Learning with Open Badges, n.d.; Mallon, 2019). OpenBadges plays a significant role in the era of digital learning, empowering students to pursue goals and earn badges that reflect their acquired skills. Digital educational badges enable students to reflect on their accomplishments and provide tangible credentials for future career opportunities, reinforcing the value of learning various subjects (Devedžić & Jovanović, 2015).

In other instances, universities such as the University of Melbourne have developed a 12-month program aimed at training employees for companies and issuing digital badge certificates for specific skill sets. While this approach is an innovative partnership between the university and organizations, it may not fully cater to the university’s currently enrolled students who are not employed by companies interested in acquiring these MicroCerts (The University of Melbourne and Belong Launch New Customised Leadership Program, n.d.).

3. Methods and Context of AchieveUp

Micro-credentialing is a subject of active research and offers more portability and flexibility to evaluate student skills beyond grades and test scores. The drive to utilize micro-credentialing is due to its ability to innovate the field of education; by evaluating skills students obtained that go beyond what current grades and or assessment scores offer to instructors. The AchieveUp interface implementation builds upon is an open-source NSF project aimed to develop measure student performance and disperse badges in a manner that has not been achieved prior. The context in this framework, is to data mine various key information from the assessments in the learning management system (LMS) to award digital badges to students that show comprehension of topics seen in a course. In this NSF project, an open-source framework for awarding and managing badges is developed far beyond what already exists. Micro-credentials provide mechanisms for quantifying student skills, abilities, and knowledge beyond traditional grades and transcripts. In the context of this project, students are awarded through digital badges obtained through data mining of their digitized assessment data. Prior research has established the legitimacy of micro-credentials as a means of assessing college readiness and connecting students’ skills to workforce demands, providing a foundation for our exploration of their potential in higher education (Wheelahan & Moodie, 2024). This framework represents a research-based approach aimed at exploring a novel methodology for tracking skills in a more granular and transportable manner. Promising results have been obtained, demonstrating the potential of this approach to provide a more accurate picture of students’ skills. Although limitations of the current implementation are acknowledged, the framework has the potential to address some of the shortcomings of traditional grading systems. As an ongoing research-based study, the methodology is continually being refined and improved, with the goal of developing a more effective and comprehensive system for assessing student skills and knowledge. This iterative process enables the identification and addressing of areas for improvement, ultimately strengthening the framework’s ability to provide a nuanced and accurate representation of student abilities.

3.1. Need for Automated Generation of Micro-Credentials

Micro-credentialing is an emerging means to authenticate an achievement, accomplishment, or even readiness to advance education (Fishman et al., 2018). It has been suggested that digital micro-credentials may increase equity and improve retention in higher education (Mah et al., 2016). Students’ acceptance of the value of micro-credentialing is a key motivating factor for earning micro-credentials which in turn can increase motivation during learning (Gibson et al., 2016). Additionally, employing micro-credentialling tools support the reshaping of higher education with a stronger emphasis on industry readiness (Wheelahan & Moodie, 2024). The BC-Eco micro-credentialing process commences as students complete their digitized quiz-based assessments, and subsequently instructor facing Python programming language scripts are used for analyzing student performance a granular approach. This operational approach provides a bottom-up alternative to traditional top-down reasoning approaches, relying on data mining and data-driven discovery instead of contextual state information and interactive cues (Amoruso et al., 2024; Hung et al., 2009). Specifically, the project reaches means to deliver and refine STEM micro-credentials through the annual cycle shown in Figure 2.

3.2. Tailoring Steps for Micro-Credentials in STEM Assessments

An iterative process is effective to develop a transportable micro-credentialing framework. Within of the Building Capacity Ecosystem (BC-ECO), the project was completed in accordance with the project plan. Activities completed include the following:

-

identifying useful Canvas API requests to attain required student data,

-

acquire Canvas user token,

-

storing a database for the user to tag questions to achievable course skills,

-

analyzing student statistics on assignments, and

-

the development of providing instructor-facing course statistics.

3.3. Advantages to Student’s and Employers

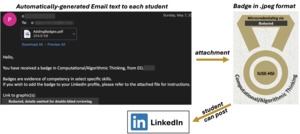

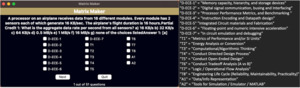

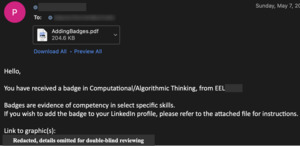

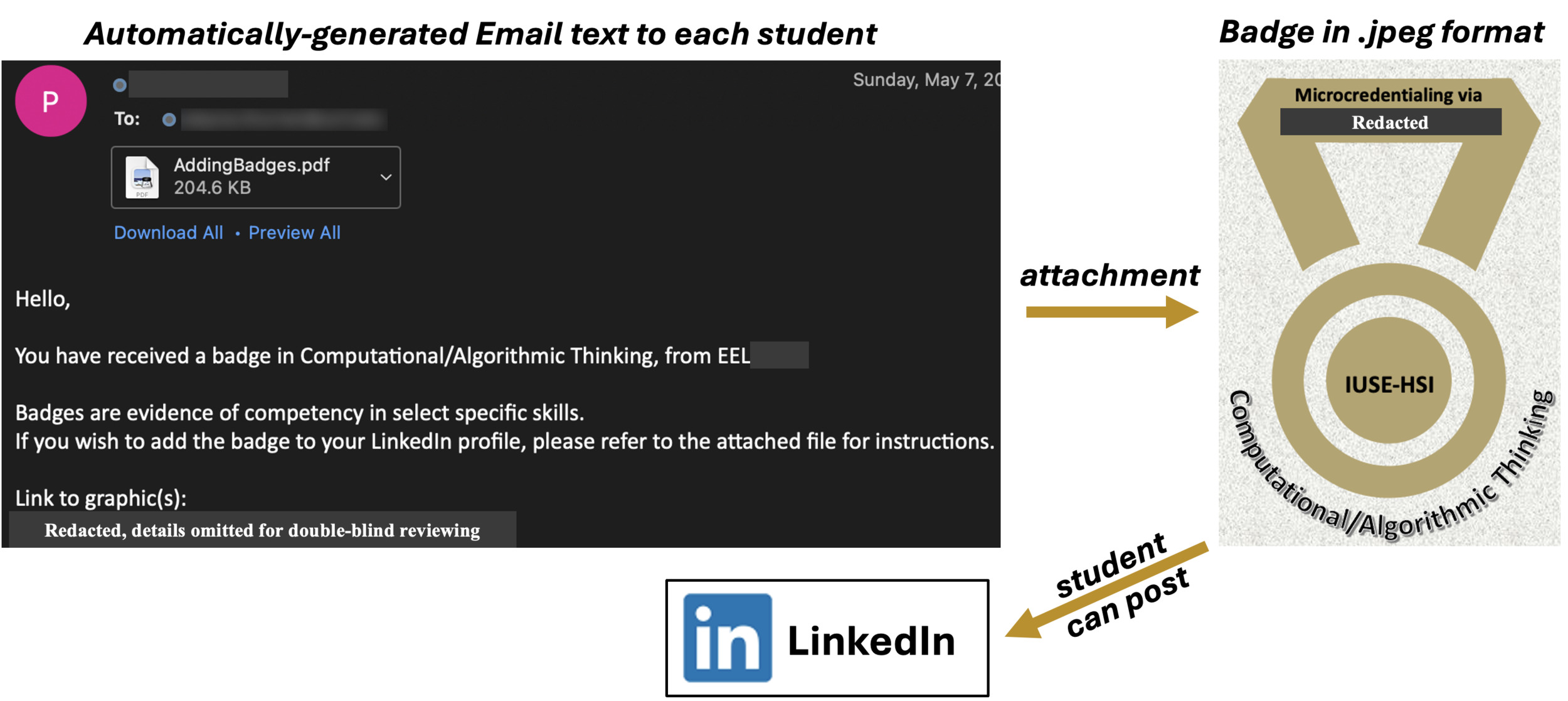

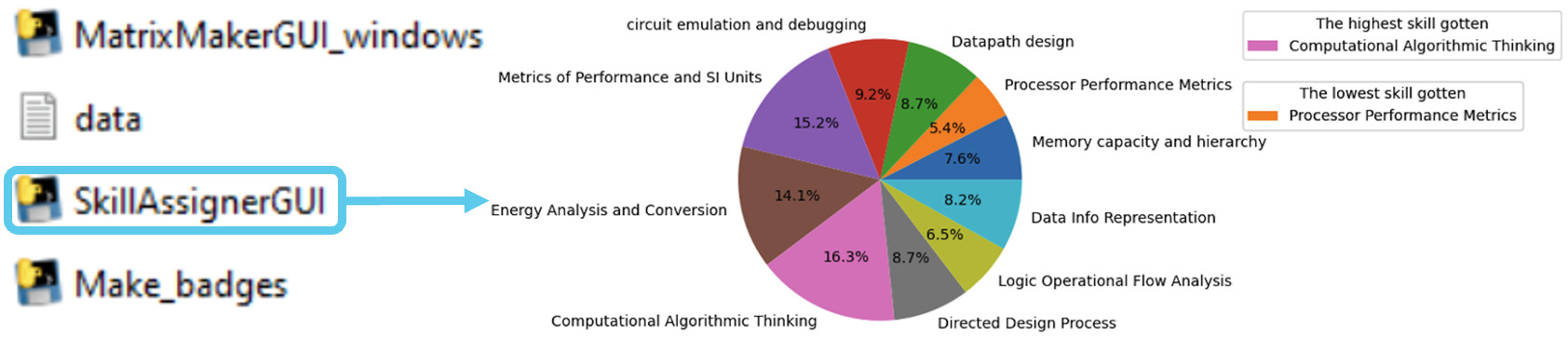

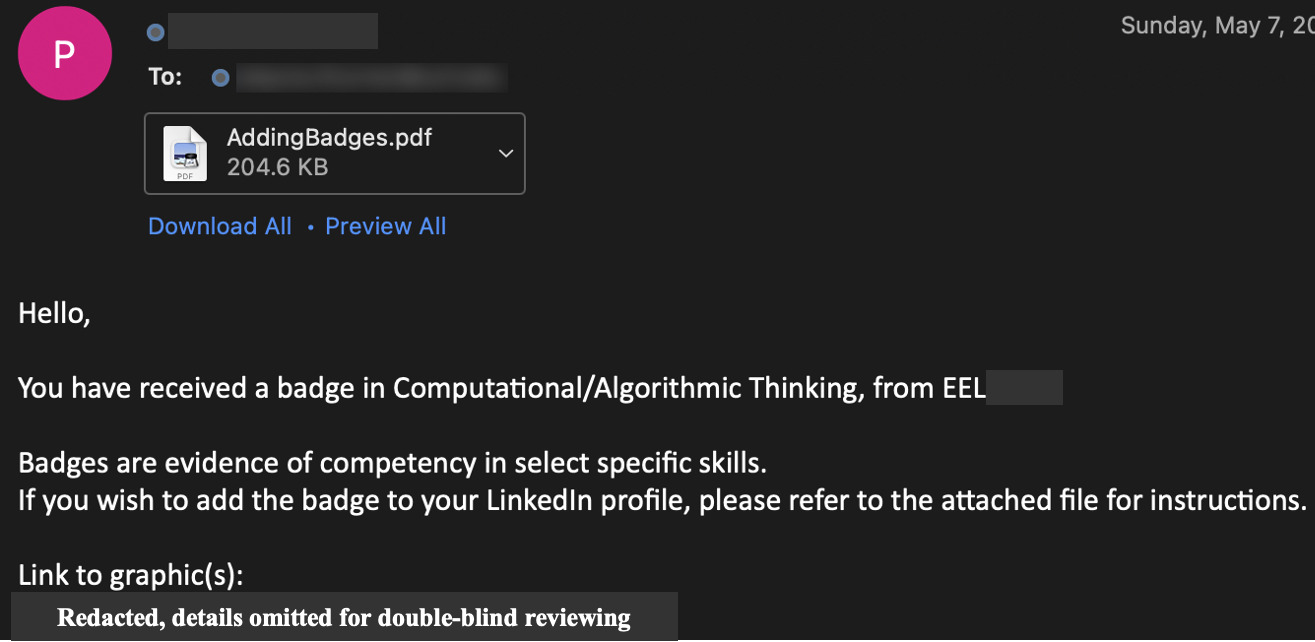

The AchieveUp toolset provides students with an incremental, achievable goal. Regardless of their traditional academic grades, students can demonstrate competency in specific skillsets and showcase this achievement on LinkedIn. This approach is distinct from traditional education formats, where GPA’s and course letter grades may not accurately reflect a student’s mastery of particular skills or content areas. By providing granularity in assessing competencies, AchieveUp enables students to highlight their strengths, regardless of their academic background. This results in a grade-agnostic evaluation process that allows employers to make informed decisions about potential employees based on their demonstrated expertise. For instance, Figure 3 demonstrates that the instructor or graduate teaching assistant (GTA) may send specific badges to student’s that demonstrated exceptional competency in a skillset. Moreover, the digital badge presented on the left side of Figure 3 represents the digital badge a student received via the email from the GTA, along with an instructional guide on adding it to the student’s LinkedIn profile.

Moreover, Figure 3 represents one of the 17 badges developed in an undergraduate electrical and computer engineering (ECE) course. Students who demonstrate outstanding understanding throughout the semester can display these badges to highlight their expertise and exceptional performance in specific areas. By visualizing student skills and achievements through digital badges, employers can gain valuable insight into a candidate’s strengths and abilities. This transparency also enables targeted tutoring and support, as students’ skill gaps are identified and addressed. For instance, an employer viewing the badge depicted in Figure 3 can appreciate that the student achieved exceptional proficiency in computational/Algorithmic Thinking.

3.4. Advantages to Instructors

Allowing instructors the ability to track skills of student’s semester wide is a huge advantage to the lecture design. There are two main points that benefit faculty, the ability to update the course based on student comprehension, and the ability to set forth a clear set of achievable skills that should be taught and received by the students. Providing only letter grades as a measure of student understanding can be limiting for instructors, as it does not reveal the depth of knowledge acquired by students. In contrast, using skill identification enables instructors to gain a clear and nuanced understanding of what students have grasped and what they may have missed. This insight allows instructors to refine their teaching approach, providing updated content or targeted tutoring to individual students who require additional support. By shifting from letter grades to skill identification, instructors can better tailor their instruction to meet the needs of all learners.

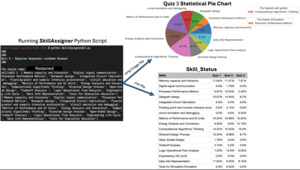

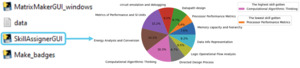

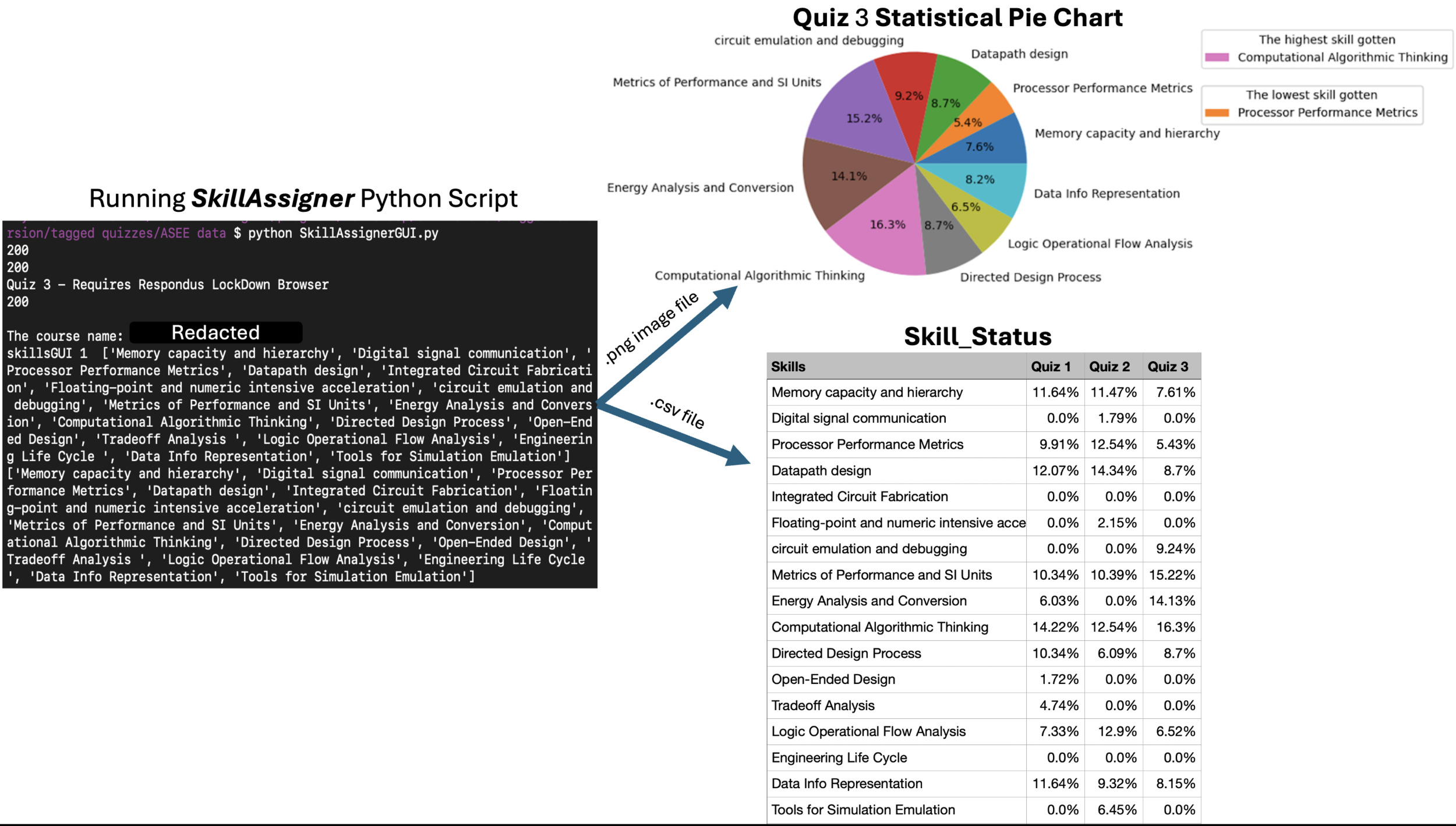

The idea behind Figure 4 was inspired by instructors who want to quickly gain insights into their students’ progress. By providing a visual representation of class performance, such as a pie chart and data matrix, instructors can easily identify areas where students are exceling or struggling. This enables them to make informed decisions about course adjustments and provide targeted support to students. During the determination phase of the toolset, this data is presented in a way that facilitates quick analysis and decision-making. The pie chart provides an at-a-glance view of skill achievement distribution, with the highest and lowest achieved skills clearly highlighted. Meanwhile, the data matrix offers a detailed breakdown of student performance across all assessments, allowing instructors to drill down into specific areas of concern or celebration. By presenting this information in a clear and concise manner, SkillAssigner supports instructors as they navigate the determination phase and make data-driven decisions about their students’ progress.

In Figure 5, three distinct patterns of skill development are observable among students as they progressed through the course. A linear acquisition trend is evident in skill T3 (Figure 5a), where student competency in this area increased uniformly throughout the semester. In contrast, skill T5 exhibits a front-loaded acquisition pattern (Figure 5b), where most students acquired this skill immediately upon initial coverage of the topic, with no further learners demonstrating it subsequently. This highlights an opportunity for instructors to target resources and support for enhancing student mastery of this skill in later course stages. Conversely, skill T6 displays a back-loaded acquisition trend (Figure 5c), where nearly all students acquired this skill at the end of the course. This finding suggests that providing additional resources or scaffolding earlier in the course may be beneficial to broaden student learning experiences and support future employer interests. Overall, the presented analysis via the AchieveUp toolset demonstrates how data mining of digitized assessments can provide valuable insights for instructors and employers alike.

4. AchieveUp Operational Flow

4.1. Operational Flow for Integrated Content, Evaluation, and Tutoring

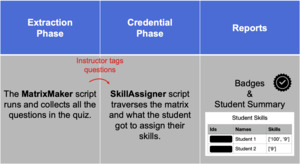

The AchieveUp framework for micro-credentialing involves three key phases: initial determination, automated dispersion, and showcasing abilities as shown in Figure 6 and presented in the three-phase process within Figure 7. To determine student competencies, AchieveUp utilizes digitized quiz-based assessments within the Learning Management System (LMS). This approach leverages the wealth of digital data generated during online quiz attempts, which is a common method for assessing student skills across courses. The automated dispersion phase then allocates badges based on this assessment data. Finally, students can showcase their abilities and access perks like personalized tutoring and remediation. Returning to Figure 2, the AchieveUp framework seamlessly guides the ecosystem from the lower-right corner of the micro-credentialing service triangle to the realm of industry internships.

The following phases are examined in greater detail:

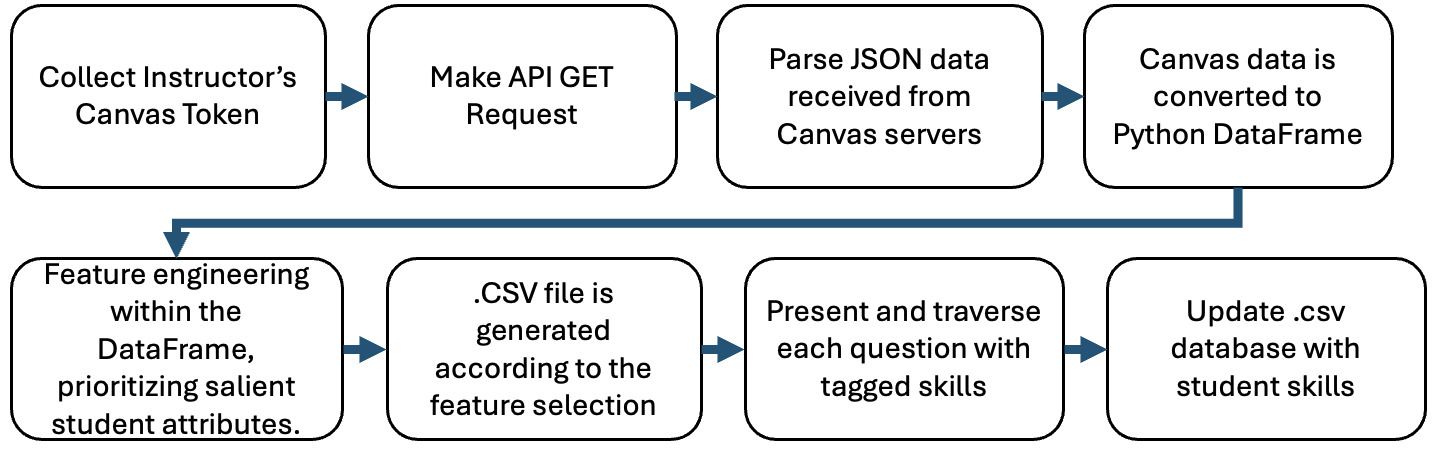

-

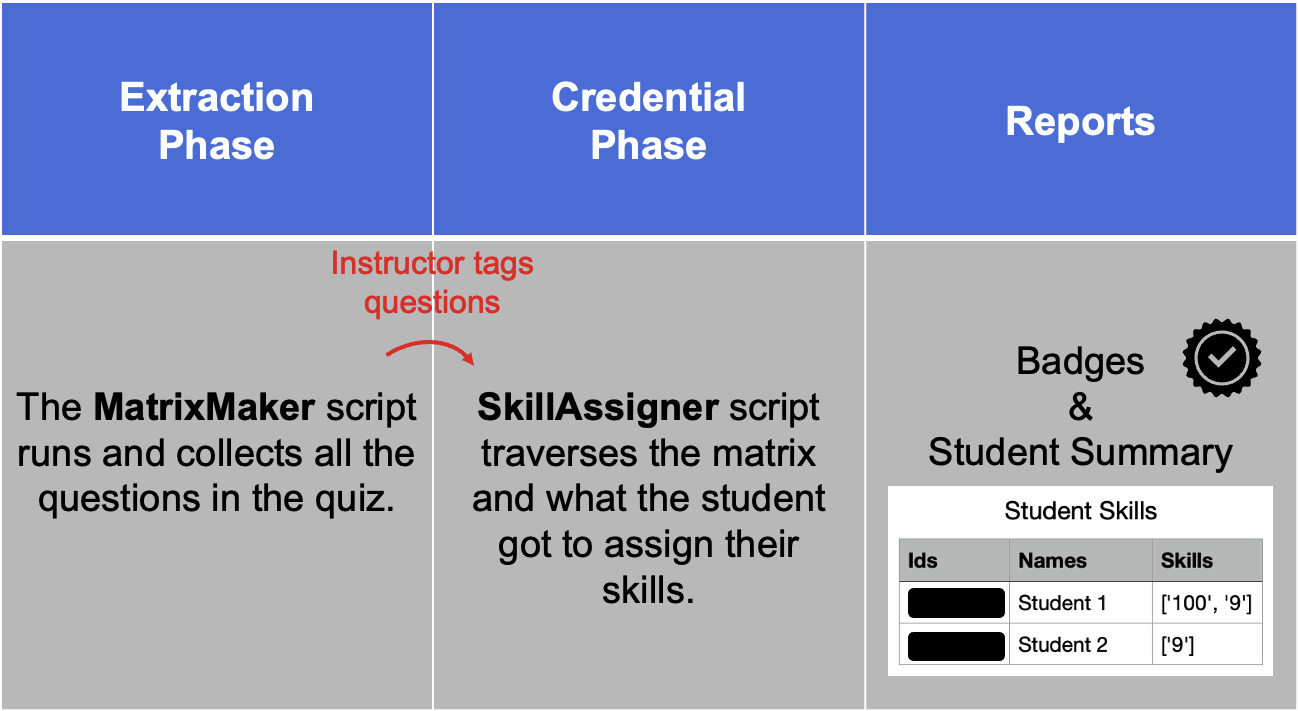

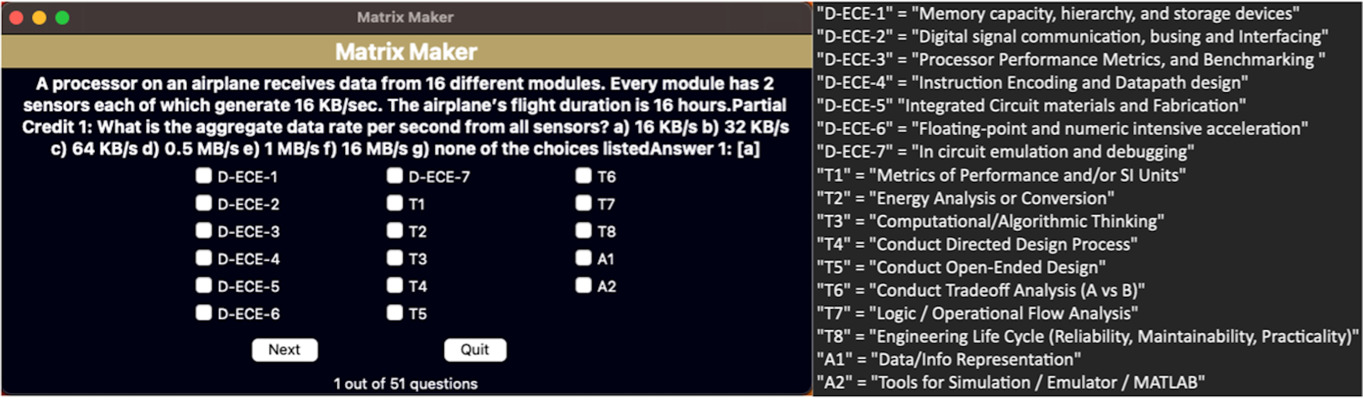

The Tagging Phase: The MatrixMaker presented in Figure 8 is a key component of the framework that facilitates tagging and organization of questions. As shown within Figure 9, its process flows from making an API request to producing a matrix of tagged questions. Initially designed as a proof-of-concept prototype, the application was intended to extract Canvas questions and store them in a way that enables skill tagging in assessments. However, this initial design required technical expertise to operate, specifically a “script overseer” such as a programming-literate graduate teaching assistant to access and run the source code. To address this limitation, significant work went into developing a user-friendly interface that would allow most STEM instructors to integrate the MatrixMaker into their Canvas LMS-based courses with ease. This redesign enabled users to simply provide course-specific URL values and a bearer access token for integration, without requiring manual tagging of questions or technical expertise. The result is a more accessible and efficient tool for educators to leverage the power of data mining in their teaching practices.

-

The Determination Phase: The SkillAssigner builds upon utilizing the API request to collect quiz statistics and the output from the MatrixMaker. The “SkillAssigner” was coined as the name of the second application that is continuously ran throughout the course of the semester for each assessment, as it follows the MatrixMaker after students have taken the given assessment. In the foundational work, the SkillAssigner was developed to data-mine the student statistics on performance for a given assessment, calculate the skills if any for each assessment, and output a matrix with each student and what skills they demonstrated (if any) for a particular quiz-based assessment. In addition, it provides instructors with data to gage the overall course performance with a list of students and their skills and an overall course performance trend data.

-

The Automatic Badge Dispersion Phase: the Automatic Badge Dispersion Phase utilizes an automatically generated report that summarizes a student’s course performance. This report serves as the basis for awarding badges, which recognize students who have demonstrated adequate competency in specific subject areas. By leveraging this application-driven approach, students can be formally recognized for their hard work and achievement, providing a tangible incentive to strive for excellence in their academic pursuits.

The AchieveUp software framework utilizes digitized quiz-based assessments on the Canvas LMS to automatically measure student skills upon completion of a given quiz throughout the semester with the presented flow in Figure 7. In this context, the term “automated” refers specifically to the automated process of measuring student skills, rather than the assessment itself being automated. Therefore, the focus of the AchieveUp framework is on leveraging digital technologies to streamline the assessment process, while still maintaining the integrity of traditional quiz-based evaluations.

4.2. Utilization of Foundational AchieveUp Software Integrated into Curriculum

To support data-driven decision-making, our NSF project has developed a Python script-based framework for analyzing student performance on a question-by-question basis. The framework outputs a CSV file listing student results, which are determined by classifying each question into specific categories, such as theoretical skill or applied skill, and then examining student responses to determine whether they meet instructor-defined criteria. For each student and badging category, the software identifies whether to award a badge based on student performance up to the threshold set by the instructor.

The AchieveUp framework consists of three primary programs utilized throughout the semester: question extraction and student performance calculation. To streamline the process, three main phases have been identified. The first phase is the extraction phase, which involves retrieving questions from the Canvas LMS to develop a data matrix that serves as the foundation for skill tagging. The second phase is the credentialing phase, which is the core of the project, as it entails traversing the question and student performance matrices to assign skills for each assessment to students. The final phase is the reporting phase, which encompasses badge dispersal and a detailed report on student-by-student skill proficiency. Notably, the framework’s ability to tabulate, calculate, and present student performance is heavily reliant on underlying matrices that are hidden from view through the user interface.

The use of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) streamlined data collection and analysis for the Micro-Credentialing Framework for Canvas. Whereas manual downloading of Canvas data was impractical due to time constraints and user inconveniences. As an alternative, APIs were used to automatically export data to the micro-credentialing application. By sending API requests, it was possible to automatically obtain the required information as well as alter data on Canvas (Canvas LMS - REST API and Extensions Documentation, n.d.). The Micro-Credentialing Framework for Canvas utilized Python programming language to support data extraction. This language offers libraries that simplify data manipulation and room for potential machine learning algorithm implementation. Specifically, the script extracts values from specific data fields within the Canvas Quiz data export format. APIs were used to collect information without manual downloading, which streamlined workflow as presented in Figure 9.

The Canvas LMS generates a JSON data file in response to an API request (Figure 9), using the API call to retrieve information about specific quiz questions, including unique IDs for each quiz. This step is crucial as it enables subsequent drilling down to individual question text strings and response text strings. To parse the JSON data, only specific fields required by each micro-credential are extracted from the entire dataset. The JSON data is then converted into a DataFrame using Panda’s library in Python, allowing for easy classification of data in a table-like structure comprising rows and columns. Student data, including IDs and names, were initially stored in a list format. A Python script is used to acquire the data while performing field remapping, resulting in the generation of a CSV file each time the script is invoked. Additionally, this enhanced capability enables students to link their micro-credentials with their LinkedIn profiles, potentially advancing internship or hiring connections with potential employers.

4.3. Digital Badge Opportunity

The badges listed in Table 3 developed for student demonstration were designed to have specific names that indicate understanding in a particular topic, while being broad enough to be relevant across similar courses. Moreover, standardization of badges may be an essential consideration in the context of digital badging systems. Future work consists of working closely with university digital learning teams to address the mutual relationship between Canvas credentials via Badgr and the AchieveUp methodology. The AchieveUp software framework is designed to be badge-agnostic, but applicable for institutions which have standardized badges. This flexibility allows the system to accommodate various badges, as long as a badge title is provided and associated with relevant assessment questions. As such, the AchieveUp framework can support diverse badging initiatives, providing a versatile platform for institutions to implement their own standardized or customized badging systems.

The methodology behind developing badges aimed to strike a balance between conciseness and visual appeal, as seen in Figure 3. For instance, the implemented ECE badges with the instructor of record consisted of 17 identical designs listed in Table 3, each specifying a skill in a digestible format. To facilitate student sharing, we host digital badges online, allowing recipients to add them to LinkedIn using a supportive feature. Each receiving student receives an email with an attached instructional guide for LinkedIn and a link to the awarded badge (Figure 3). In addition, our processes for measuring topic competency rely on skills associated with each question after instructors or graduate teaching assistants (GTAs) tag skills using MatrixMaker. The MatrixMaker, displayed on the left-hand side of Figure 10, maps skill options to the right-hand side.

4.4. Algorithmic Framework for Micro-Credentialing Skill Quantification

The approach to measuring student skill competency is designed to provide a comprehensive assessment of their abilities, rather than relying on a single-question or distinct evaluation processes such an oral exam. Although our approach is not exhausted with certifying a skill, it adds an increasing resilience because responses to questions throughout a course, or even multiple courses are used to award micro-credentials. Without loss of generality, letter grades are issued based on student performance to a selected ensemble of evaluation assessment questions selected by the instructor, therefore, in a sense we are applying this same approach to a micro-level than the standard macro-course level. To ensure that students have consistently demonstrated their understanding of a particular skill, a correct response rate of at least 90% is required across multiple quizzes throughout a course. This is accomplished by correctly answering questions that are specifically tagged to the relevant skill, allowing for confirmation that students have a thorough grasp of the material. By evaluating student performance across multiple assessments, mastery of specific skills can be confidently attested, rather than simply relying on a single question or assessment. More Specifically, the algorithmic approach for identifying if a student receives a badge can be represented via Equation 1:

Badge Earned = Skill Correct Responses Skill Questions Attempted ≥0.9 AND QuizMastery ≥3

Where:

-

Skill Correct Responses = Number of correct answers to questions about a specific skill on each quiz

-

Skill Questions Attempted = Total number of questions about the skill that the student attempted on each quiz

-

QuizMastery = Number of quizzes where the student demonstrated mastery of the specified skill (i.e., answered at least 90% of questions correctly)

The framework’s use of a “fuzzy threshold” ensures accurate competency identification, with a metric that can be represented by an equation. Specifically, a threshold of 90% accuracy over three assessments has been established as an effective means of minimizing noise and maximizing the validity of competency identification. This empirical determination provides a foundation for the framework’s ability to accurately identify student competencies despite potential sources of error. As a research-based methodology, continuous refinement and improvement are ongoing, allowing for further optimization of the approach and ensuring that it remains a robust and reliable measure of student skill mastery. AchieveUp adopts a refined approach to skill analysis, one that mirrors the principles of item response theory. By analyzing individual questions and their connection to specific skills, AchieveUp provides a granular measurement of a student’s abilities, aligning with the learning objectives set by instructors and course designers.

4.4. Comprehensive Illustration of a Course Configuration

The implementation of AchieveUp within a Canvas-based course can be accomplished in 7 steps, with three steps that can be completed as a one-time setup and reused for multiple semesters of the same course. Herein, this section provides an example of a step-by-step process to identify student skillsets in a course. The protocol for generating badges involves a series of sequential steps:

-

Obtain token

-

List skill names achievable within the course

-

Select a digitized quiz ID and add it to the data file

-

Run MatrixMaker and tag each question with skills

-

Run SkillAssigner on the selected quiz

-

Repeat steps 4 and 5 throughout the semester

-

Run MakeBadges application to disperse badges to students

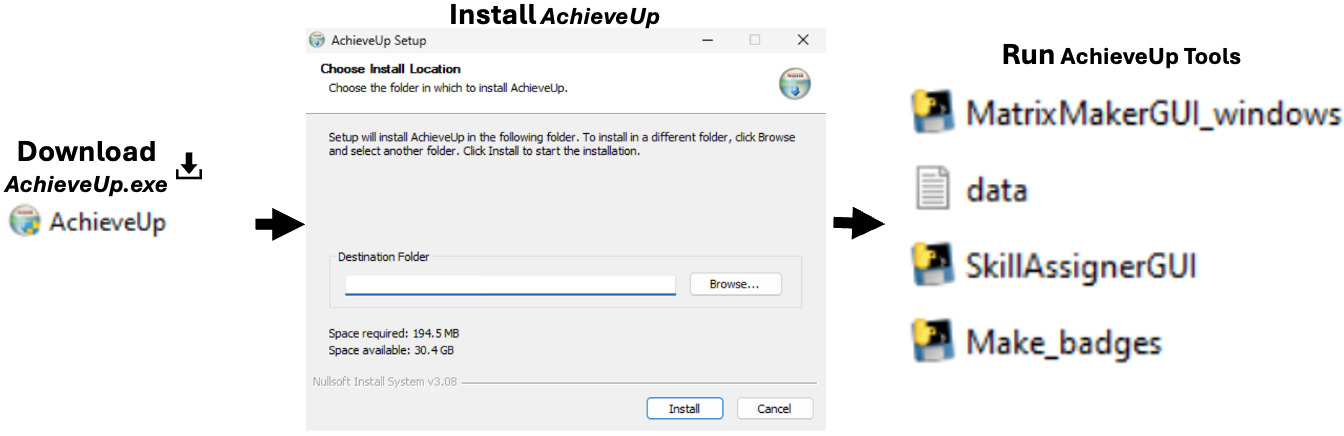

Upon installing the AchieveUp framework, visualized in Figure 11, a folder named “AchieveUp” is created, containing the respective applications. The AchieveUp folder consists of four files, three executable files and a data file, all of which are essential for implementing the micro-credentialing toolset.

The first step in implementing the AchieveUp framework is to obtain a user token from the Canvas LMS. This token enables AchieveUp to perform API requests and collect data, thereby facilitating the implementation of the micro-credentialing toolset. Furthermore, presented within Figure 12, a step-by-step process is presented in order to extract an Access Token within the Canvas LMS website.

To prime the MatrixMaker, the instructor or teaching assistant must identify and specify badge names or labels, which are then fed to the MatrixMaker list of options to select from, when tagging individual questions. This step is essential in ensuring that the MatrixMaker is properly configured to identify and assign skills to student responses. As described within Figures 9 and 13, to access course and student data and tag questions, the instructor or teaching assistant must paste their token into the data file, assessment identification, and specify the list of achievable skills in the course.

Once the token is provided and the list of skills is specified, the user runs the MatrixMaker application to tag the questions within the assessment as presented in Figure 10 and 14. The MatrixMaker application enables instructors to identify and assign skills to student responses, thereby providing a comprehensive view of student skillsets.

To facilitate ongoing assessment of student skills throughout the semester, Step 5 involves executing the SkillAssigner application subsequent to each student’s completion of a digitized quiz. As illustrated in Figure 15, upon running the SkillAssigner after the quiz 1 in an electrical and computer engineering course (ECE), the application generates a visually intuitive pie chart that provides an aggregate representation of the class’s performance with respect to the skills targeted by the given digitized quiz. This graphical output enables instructors to readily discern the distribution of student proficiency across the assessed skills, thereby informing subsequent instructional decisions.

The badge awarding and generation process is initiated upon completion of the semester or at the instructor’s discretion, utilizing the Make_Badges application presented within Figure 11. This application generates a list of automated, pre-formatted emails tailored to each student who has earned at least one badge, as visualized in Figure 3 and Figure 16.

5. Evaluations and Perceptions

5.1. Impact on learning and Achievement

Remediation offers an opportunity for instructors and TAs to target and remediate specific skills, while also enabling students to provide feedback on the course through one-on-one conversations with TAs. This feedback is then shared with instructors to inform tailored teaching approaches. As illustrated in Table 4, data suggests that lecture closures had a significant impact on student engagement with digital badges. In Spring 2022, nearly half of enrolled students received at least one digital badge; however, this trend was not sustained in the following semester. Several factors may have contributed to this outcome. One key difference was the unexpected number of lectures canceled due to holidays, university events, and Hurricane Ian’s closure. Additionally, the transition to New Quizzes for the second quiz resulted in inaccurate grading for many students. Furthermore, the research framework does not support analysis using Canvas’s New Quiz format, making it difficult to track student performance on the second quiz for Fall 2022. Consequently, student comprehension of the eight skills assessed in the second quiz could not be demonstrated.

5.2. Correlation Between Badges and Grades

The micro-credentialing research was developed and tested through a couple semesters, and among that time, badge dispersal was implemented to reward high achieving students that deserve recognition on the skills they obtained in the course. Micro-credential badges give students something to look forward to throughout the semester as achievable goals, this also gives students with the ability to promote themselves in the industry to employers after acquiring digital badges from a course. In two separate semesters and observed that about half of the students were qualified enough to receive at least one badge to say they were proficient enough to claim proficiency in a particular part of the course material in the first semester. Building on the normalized statistical data from the grade-badge hierarchy presented in Figure 17, quantitative analysis revealed a statistically significant correlation between badge acquisition frequency and course performance. Specifically, students achieving “A” grades earned 62.2% of the badges. In contrast, those with “B+”, “B”, and “B-” grades collectively received an average of 16.9% of the badges.

In continuation with developing a greater understanding of the connection between the students receiving badges and the course points they received throughout the semester; Figure 17 presents a visual representation of a statistical analysis. Given that the analysis may vary slightly from course to course, it is important to understand that while the highest achieving students receive the greatest number of badges, other students with a lower grade were still able to retrieve badges on topics that they exceled in. Allowing for the motivation of students to get credit for what they demonstrated high competency with as obtain trackable goals. Although stronger students may be more likely to earn badges, the data presented in Figure 17 indicate that students from diverse academic backgrounds are capable of earning and showcasing badges on LinkedIn. This finding suggests that the badge system has a motivational impact on students across a range of abilities, fostering engagement with course material irrespective of prior academic performance.

The framework provides a meaningful way to recognize students’ skills through the use of online assessments, which can generate transportable badges that demonstrate students’ abilities in a detailed and accurate manner. This approach has the potential to provide more value to employers and educators than traditional grading systems by offering a more nuanced understanding of student competencies. Badges are awarded based on consistent proficiency demonstrated through semester-wide question responses, rather than a single assessment. The rigor of this approach is evident in that not all students receive badges, and even top-performing students do not receive all possible badges. As a result, the badges disseminated through this framework provide a granular insight into students’ actual strengths, offering a more comprehensive and accurate representation of their skills and abilities. Additionally, as part of a major curriculum revision, the ECE department is exploring the potential for an exit examination in the final semester of bachelor’s studies. This examination could serve as a validation mechanism for the badging process, particularly with regards to the 90% threshold used in AchieveUp’s algorithmic approach. Furthermore, as part of this revision, future employers will be providing feedback through surveys, which will inform our ABET accreditation efforts and help ensure that our micro-credentials are aligned with industry needs.

5.3. Perceptions from Instructors and Students

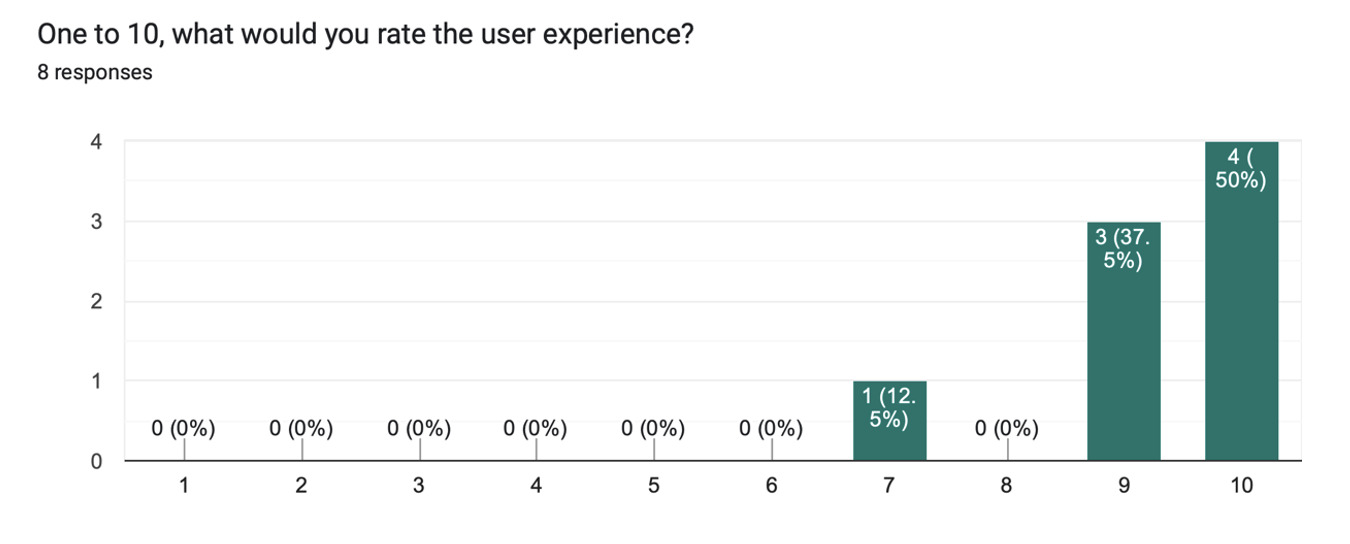

In validating the application of AchieveUp withing university already established course structures, instructors were provided a Google review form, and students received a Qualtrics survey via an external reviewer. Within various engineering departments a survey was dispersed to instructors that received a user manual and short demonstration of the AchieveUp toolset. After instructors received training on how to use the software and overview the interface, survey results demonstrated that 62.5% of instructors were highly likely to implement the AchieveUp framework in their courses as a micro-credentialling application. Moreover, instructors overwhelmingly expressed encouraging viewpoints of AchieveUp, with 87% rating 9 or 10 out of 10 for user experience on a Likert scale presented within Figure 18.

The reviews presented in Figure 18, incentive AchieveUp’s objective of implementing a globally scaled skill analysis with minimal course modification. Furthermore, an external evaluation of the research grant, based on student surveys, indicated that micro-credentialing had moderate extent when perceived as helpful in supporting internship acquisition, self-efficacy development, and the formation of a professional STEM identity (Lee-Thomas et al., 2024). The survey-based feedback provides initial evidence of the potential benefits of the framework, offering valuable insights into its effectiveness. While this methodology has its limitations, it serves as a foundational step in evaluating the framework’s impact. To further establish the efficacy of the approach, more rigorous evaluation methods, such as randomized controlled trials, can be employed in future studies to provide more robust and reliable evidence of the framework’s benefits and potential areas for improvement. Moreover, micro-credentialing skill analysis has the potential to be a valuable asset for higher education institutions seeking to differentiate themselves through industry connections, providing a unique opportunity to demonstrate the relevance and applicability of students’ skills to real-world contexts.

5.4. Retroactive Skill Profiling via Back-Badging Analysis

The AchieveUp framework offers a unique advantage in assessing student skill competencies by leveraging existing data from quizzes within the Canvas LMS. This approach enables reactive implementation of skill identification, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of student learning outcomes. Unlike traditional micro-credentialing solutions that require a structured sequence of assignments and modules to measure skills, AchieveUp facilitates a scalable and flexible method for assessing skills throughout the semester. Moreover, this framework can be easily updated to accommodate changes in course content and assessments from one semester to another. As demonstrated in Table 5, which presents the results of “back-badging” in 10 semesters of an ECE course, AchieveUp’s adaptive approach enables educators to retrospectively analyze student performance and identify areas of strength and weakness.

The back-badging analysis revealed significant variability in skill acquisition among students across different sections, with an average of 1.75 to 2.44 skills per student. Notably, certain skills emerged as particularly prominent, including Directed Design Process, Datapath design, Data Info Representation, and Metrics of Performance and SI Units. Furthermore, the analysis highlighted the impact of external factors on student learning outcomes, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the Spring 2020 semester, which was affected by the pandemic, exhibited a less dispersed distribution of badges due to reduced quiz and lecture activity, as well as adjustments to the course modality. These findings underscore the importance of considering contextual factors when interpreting student performance data and demonstrate the value of AchieveUp’s flexible and adaptive approach to skill assessment.

6. Conclusion

To support student success in a required undergraduate electrical and computer engineering course, a workflow was developed and integrated for providing grade remediation and tailored tutoring. This workflow enables instructors and teaching assistants to easily implement peer-based tutoring schemes, which provide targeted support to students who need it most. Student feedback has been overwhelmingly positive, with many appreciating the opportunity to receive individualized attention and guidance from peers and teaching assistants alike. Additionally, student survey data suggests a moderate association between micro-credentialing and enhanced internship acquisition, professional self-efficacy, and STEM identity development. Consequently, the workflow’s seamless implementation has helped to improve student outcomes in the course.

AchieveUp’s Micro-Credentialling is closely integrated with the BC-ECO segment, particularly remediation, where students consult with tutors to discuss their assessments. Each component of the BC-ECO aims to enhance student learning, with the effects reflected in the badges received by students. The current phase of research in the project is focused on receiving helpful quantitative analytics from various university courses that comprise of different topics. For instance, utilization of AchieveUp into a Heat Transfer course within the department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering (MAE) and Statics courses within the Civil, Environmental, and Construction Engineering (CECE) Departments are in various stages of integration. Meanwhile a thrust at university level is being pursued for a standardized Canvas plugin integration. Optionally, the Python programming language scripts developed are available upon request.

The selection of micro-credentialing as a solution was consequence of current limitations associated with targeted tutoring and identifying what skills students demonstrate exceptionally well in. This approach was motivated by the support of instructors in various departments and attempts made by related work with companies developing platforms that associate skills to modules or assessments, as well as research approaches focusing on student engagement with course topic material. AchieveUp uses a data-driven approach to process program operations. It involves using functions like REST API calls to gather and save essential data from the course, including user info, assessment questions, and student performance metrics. In addition, a fuzzy threshold approach was utilized to determine student’s that are to be reworded digital badges for display.

Instructors in various departments were surveyed on the AchieveUp toolset for perspectives on potential implementation. Survey results showed that majority of instructors interviewed were highly likely to implement the AchieveUp framework in their courses as a micro-credentialling application. Moreover, instructors overwhelmingly expressed positive views of AchieveUp, with 87% assigning a rating of 9 or 10 out of 10 for user experience on a Likert scale. The results of the quantitative analyses did not uncover any inconstancies between badge issuance and overall student achievement. Although this finding may be expected, it serves as a foundational step in establishing the validity of the framework. As an ongoing research-based study, the methodology is continually being refined and improved, with plans to explore more advanced statistical techniques in future studies to examine causal relationships and potential confounding variables. This will enable a deeper understanding of the complex interactions between badge earnings, academic performance, and other factors, ultimately strengthening the evidence base for the framework’s effectiveness.

Figure 8 and 9 illustrates the path taken to improve modern STEM education by leveraging student digital data in an innovative way for classification of skillsets. Specifically, digitized quiz-based assessments enable the determination of skills, which are then dispersed among students for recognition, promotion, and tailored remediation. In conclusion, it is recommended that educators across various disciplines, particularly those within STEM, adopt innovative approaches that motivate student participation and provide analytical data to support research of evaluating instructor effectiveness. As both students and educators face significant challenges in today’s educational environment, it is essential that we harness emerging technologies to facilitate collaborative learning experiences and enhance student outcomes. By leveraging these tools and approaches, we can empower our students with the knowledge, skills, and competencies necessary for success in the 21st-century workforce.

In the current study, badges were awarded at the conclusion of the semester, and students’ academic performance was evaluated traditionally using letter grades. Although the implementation did not provide real-time feedback on skill proficiency to students during the semester, the findings indicate that the badge system can serve as a motivator for students. As the application was primarily designed for instructor use, data was not collected on the direct correlation between badge usage and academic achievement. However, this represents an important area of investigation for future research. A potential direction for future studies could involve comparing student outcomes with and without badge-based motivation to more fully elucidate the relationship between badge usage and academic achievement. Additionally, as part of the future work, we have requested the Institutional Knowledge Management (IKM) team to analyze ECE course student performance, including longitudinal tracking over upcoming semesters and retrospective analysis of the past 10 semesters, to inform our understanding of student progression. Furthermore, AchieveUp has the potential to provide a more personalized learning experience for students by leveraging digitized quiz-based assessments to generate badges that are tailored to individual students’ skills and knowledge gaps. The skill identification process aims to strike a balance between specificity and breadth, identifying skills that are distinct from generalized course topics while remaining relevant to future employers and connected to skills that can be built upon in other courses. This approach can be used in conjunction with other pedagogical methods to provide a more comprehensive understanding of students’ learning trajectories, allowing for a more nuanced and effective assessment of student progress. By combining the benefits of personalized badge generation with a balanced skill identification process, the framework aims to offer an adaptive tool for supporting student learning and development.

___482265_.png)

_linear_skill_acquisition__(b)_fron.png)

.png)

___482265_.png)

_linear_skill_acquisition__(b)_fron.png)

.png)